This means that while you are taking into account all of the cool things that you will build—the yards, the mountains, the interchanges, the industries—they will always be subject to the bigger, overriding concern of how much room you have in which to build.

If you have only 100 square feet in which to work, you might plan a small, narrow gauge layout. But you will always need a few extra feet to fit in that stamping mill or the interchange to the Class I railroad.

If you have 500 square feet available, you might plan a small section of a division of a big, urban railroad. But you will always need a few extra feet for that staging yard or for the lift bridge across the river in the center of town.

If you have 5000 square feet available (and who has that much room?), you might plan to build an entire division of a Class I railroad as it drives across the Midwest. But you will always need a few extra feet for wide enough aisles to accommodate the 25-man operations crew such a railroad would require.

So the essence of model railroad planning is making deft compromises. It is one thing to plan a layout that is a decent rendition of a portion of some real or imagined prototype. The trick is to include sufficient scenic and operational elements for it to look and run well, along with sufficient space for the people who will need to see it, access it, and run it. But each thing you add detracts from some other thing. It turns out that the solution rarely yields to brute force.

When I spent a few years playing around with high powered model rockets I learned this very same lesson, and it’s the one that NASA wrestles with every day. You start with a sim

ple cardboard tube and a few grams of black powder as propellant. But to bring the rocket safely back to earth you install a parachute “retrieval subsystem.” That subsystem gets the rocket back to Earth in one piece, but it adds weight to the rocket, so you need a slightly more powerful motor. The more powerful motor demands a bigger hull. The bigger hull requires a bigger parachute. The bigger rocket is more sensitive to the timing of the retrieval subsystem, so you need to add a digital G-force sensor to fire the retrieval subsystem precisely at apogee. That digital G-force sensor is expensive, so you add a manual back up system. Both of those systems add weight, so you need a bigger motor, which requires a bigger hull, and around you go, with each system impacting each other system, ad infinitum.

ple cardboard tube and a few grams of black powder as propellant. But to bring the rocket safely back to earth you install a parachute “retrieval subsystem.” That subsystem gets the rocket back to Earth in one piece, but it adds weight to the rocket, so you need a slightly more powerful motor. The more powerful motor demands a bigger hull. The bigger hull requires a bigger parachute. The bigger rocket is more sensitive to the timing of the retrieval subsystem, so you need to add a digital G-force sensor to fire the retrieval subsystem precisely at apogee. That digital G-force sensor is expensive, so you add a manual back up system. Both of those systems add weight, so you need a bigger motor, which requires a bigger hull, and around you go, with each system impacting each other system, ad infinitum.Once you start up that ladder of complexity, the complexity required to support the complexity grows ever more complex. If NASA could add in all of the safeguards required to create a foolproof space shuttle, it could never be built and would never get off of the ground. All spacecraft must therefore make complex compromises in order to be effective. And the same is true for model railroad planning.

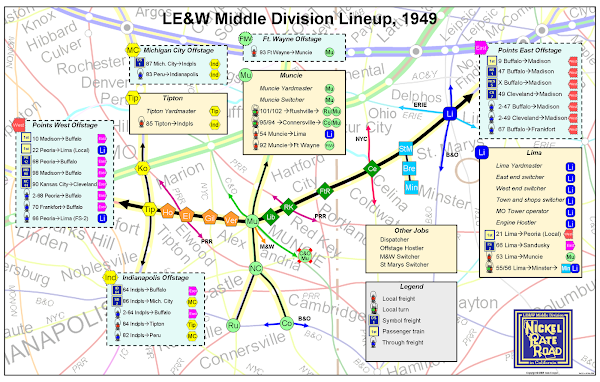

I want to model one division of one district of one modest sized railroad. It represents about 140 miles of flat, Midwestern terrain. What’s more, I intend to have lots of room in which to build it; about 2500 square feet. That’s about the size of the average three-bedroom house. That is more room than most model railroad clubs have, let alone most individuals. And yet the main thing I must grapple with in my planning is compromise.

1 comment:

Next time you're in the land of the Daley War Machine, Inc., I'll show you a 6000+ sq ft home layout. 19.5 scale miles per deck, two decks, 5000 linear feet of track in the helix (four tracks).

The art of compromise is not strong with that one! Of course, coming up witht he 26 people needed to run the fool thing is a bit problematic...

Post a Comment