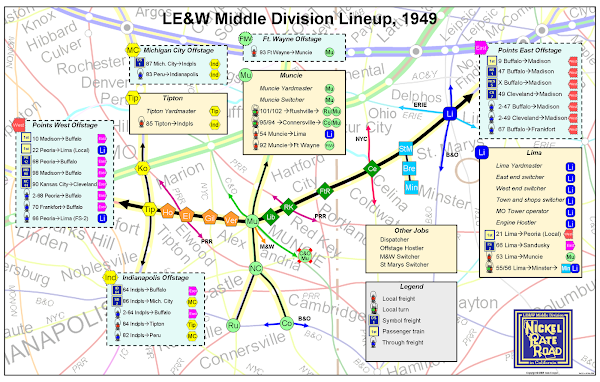

I’m modeling the Nickel Plate Railroad as it was in 1949. Actually, I’m modeling just one portion, called a division, of just one section,  called a district, of the Nickel Plate. My district was the former Lake Erie & Western Railroad, acquired by the NKP in 1926, and thenceforth designated the Lake Erie & Western District. The division I’m modeling is called the Middle Division. It’s not exactly the same as the Middle Division of the old LE&W, because at the time of the acquisition the division boundaries of the LE&W were jiggered somewhat to fit into the existing division structure of the NKP, but the name stayed. The Middle Division runs eastward from Frankfort, Indiana, to Lima, Ohio, a distance of about 140 miles.

called a district, of the Nickel Plate. My district was the former Lake Erie & Western Railroad, acquired by the NKP in 1926, and thenceforth designated the Lake Erie & Western District. The division I’m modeling is called the Middle Division. It’s not exactly the same as the Middle Division of the old LE&W, because at the time of the acquisition the division boundaries of the LE&W were jiggered somewhat to fit into the existing division structure of the NKP, but the name stayed. The Middle Division runs eastward from Frankfort, Indiana, to Lima, Ohio, a distance of about 140 miles.

I model in HO scale, which is a ratio of 1 to 87. In HO scale an average person would stand about ½ inch tall. That means that one mile of track in HO is 5280 (the number of feet in a mile) divided by 87 or 60.7 feet. To model just the Middle Division, I’d need 8,500 linear feet of track!

Model railroaders use a concept they call “selective compression,” by which they can save lots of space yet still capture the essence of a thing in a model. Basically, you model the visually unique and operationally significant parts of things, while severely truncating or eliminating portions that are either not operationally significant or visually redundant.

For example, a huge meat packing plant might be six stories high and 200 feet square, served by 6 tracks. A good model of it could be four stories high and 50 by 100 feet, served by three tracks. The spirit of the industry is retained while the footprint is dramatically reduced.

The place where selective compression is practiced more than anywhere else is along the mainline. For example, the tangent (straight) track between two towns is cut from 15 miles to a fraction of one mile. The trackage in the towns themselves would also be selectively compressed, but typically by a much smaller amount. In other words, from a modeler’s point of view, the scenery and trackage within the town is of much more interest than the scenery and trackage between the towns.

I’ve been planning to fit my model of the Middle Division into a room approximately 50’ by 50’, or 2500 square feet. By any model railroad standard that is a room of Brobdingnagian proportions. I’ve never even seen a home layout that big anywhere. But even with that generous amount of room, I’ll be lucky to fit one tenth of it in!

Years ago, model railroads were of for the most part imaginary railroads constructed on enormous tabletops and the track looped over, under, around, and through. Trains of every type and description swarmed over the landscape while the proprietor sat at a large electrical control console and sent the trains where he desired. An observer was hard pressed to know where a train would emerge once it entered one of the many tunnels visible. This style of layout is seriously out of date, and has been largely discredited, and is now referred to as “spaghetti bowl” design.

and description swarmed over the landscape while the proprietor sat at a large electrical control console and sent the trains where he desired. An observer was hard pressed to know where a train would emerge once it entered one of the many tunnels visible. This style of layout is seriously out of date, and has been largely discredited, and is now referred to as “spaghetti bowl” design.

In recent years modelers have placed far more emphasis on duplicating actual prototype railroads and the actual landscape they traverse. What’s more, many modelers, me included, are focused particularly on duplicating the same operating practices the prototype followed with as much fidelity as possible. In other words, we build a model of a specific railroad, and then we operate it like the specific railroad did. Interestingly, operations can be selectively compressed just like scenery or trackage.

Contemporary layout design utilizes a couple of principles that have sufficiently demonstrated their superiority for realism, construction simplicity, and operational verisimilitude. In particular, layouts are built as relatively shallow shelves, and the mainline of the track only passes through each shelf once. Some people call this type of layout a “sincere shelf.” Of course, there are myriad exceptions and variations to these principles, but I’ll avoid them for clarity.

their superiority for realism, construction simplicity, and operational verisimilitude. In particular, layouts are built as relatively shallow shelves, and the mainline of the track only passes through each shelf once. Some people call this type of layout a “sincere shelf.” Of course, there are myriad exceptions and variations to these principles, but I’ll avoid them for clarity.

The primary advantage of the sincere shelf is that an operator can walk along with his train, more easily imagining that he is inside the locomotive because the limits to what he can physically see are very similar to what an engineer inside the locomotive’s cab could see. The single track running through a narrow strip of landscape is the moral equivalent of what the real engineer is aware of as he proceeds down the right of way.

Whatever ultimate size and shape my model railroad will be, it will be composed mostly of a very long sincere shelf. It will likely be wrapped around itself in some spiral fashion in order to make the best use of the space. While real railroads go from one point to another in basically a straight line, few of us have model railroad rooms that are eight feet wide and 1000 feet long.

I have learned much about model railroad planning as a result of the many, many (some would claim too many) track designs I have made. Most model railroads occupy only a couple hundred square feet of space, and the lessons such layouts teach us are commonly known. Because I am planning to build a much, much larger model layout, I’m encountering some lesser known problems and opportunities. It is my intention to record those lessons in this blog, so stay tuned.

called a district, of the Nickel Plate. My district was the former Lake Erie & Western Railroad, acquired by the NKP in 1926, and thenceforth designated the Lake Erie & Western District. The division I’m modeling is called the Middle Division. It’s not exactly the same as the Middle Division of the old LE&W, because at the time of the acquisition the division boundaries of the LE&W were jiggered somewhat to fit into the existing division structure of the NKP, but the name stayed. The Middle Division runs eastward from Frankfort, Indiana, to Lima, Ohio, a distance of about 140 miles.

called a district, of the Nickel Plate. My district was the former Lake Erie & Western Railroad, acquired by the NKP in 1926, and thenceforth designated the Lake Erie & Western District. The division I’m modeling is called the Middle Division. It’s not exactly the same as the Middle Division of the old LE&W, because at the time of the acquisition the division boundaries of the LE&W were jiggered somewhat to fit into the existing division structure of the NKP, but the name stayed. The Middle Division runs eastward from Frankfort, Indiana, to Lima, Ohio, a distance of about 140 miles.

I model in HO scale, which is a ratio of 1 to 87. In HO scale an average person would stand about ½ inch tall. That means that one mile of track in HO is 5280 (the number of feet in a mile) divided by 87 or 60.7 feet. To model just the Middle Division, I’d need 8,500 linear feet of track!

Model railroaders use a concept they call “selective compression,” by which they can save lots of space yet still capture the essence of a thing in a model. Basically, you model the visually unique and operationally significant parts of things, while severely truncating or eliminating portions that are either not operationally significant or visually redundant.

For example, a huge meat packing plant might be six stories high and 200 feet square, served by 6 tracks. A good model of it could be four stories high and 50 by 100 feet, served by three tracks. The spirit of the industry is retained while the footprint is dramatically reduced.

The place where selective compression is practiced more than anywhere else is along the mainline. For example, the tangent (straight) track between two towns is cut from 15 miles to a fraction of one mile. The trackage in the towns themselves would also be selectively compressed, but typically by a much smaller amount. In other words, from a modeler’s point of view, the scenery and trackage within the town is of much more interest than the scenery and trackage between the towns.

I’ve been planning to fit my model of the Middle Division into a room approximately 50’ by 50’, or 2500 square feet. By any model railroad standard that is a room of Brobdingnagian proportions. I’ve never even seen a home layout that big anywhere. But even with that generous amount of room, I’ll be lucky to fit one tenth of it in!

Years ago, model railroads were of for the most part imaginary railroads constructed on enormous tabletops and the track looped over, under, around, and through. Trains of every type

and description swarmed over the landscape while the proprietor sat at a large electrical control console and sent the trains where he desired. An observer was hard pressed to know where a train would emerge once it entered one of the many tunnels visible. This style of layout is seriously out of date, and has been largely discredited, and is now referred to as “spaghetti bowl” design.

and description swarmed over the landscape while the proprietor sat at a large electrical control console and sent the trains where he desired. An observer was hard pressed to know where a train would emerge once it entered one of the many tunnels visible. This style of layout is seriously out of date, and has been largely discredited, and is now referred to as “spaghetti bowl” design.In recent years modelers have placed far more emphasis on duplicating actual prototype railroads and the actual landscape they traverse. What’s more, many modelers, me included, are focused particularly on duplicating the same operating practices the prototype followed with as much fidelity as possible. In other words, we build a model of a specific railroad, and then we operate it like the specific railroad did. Interestingly, operations can be selectively compressed just like scenery or trackage.

Contemporary layout design utilizes a couple of principles that have sufficiently demonstrated

their superiority for realism, construction simplicity, and operational verisimilitude. In particular, layouts are built as relatively shallow shelves, and the mainline of the track only passes through each shelf once. Some people call this type of layout a “sincere shelf.” Of course, there are myriad exceptions and variations to these principles, but I’ll avoid them for clarity.

their superiority for realism, construction simplicity, and operational verisimilitude. In particular, layouts are built as relatively shallow shelves, and the mainline of the track only passes through each shelf once. Some people call this type of layout a “sincere shelf.” Of course, there are myriad exceptions and variations to these principles, but I’ll avoid them for clarity.The primary advantage of the sincere shelf is that an operator can walk along with his train, more easily imagining that he is inside the locomotive because the limits to what he can physically see are very similar to what an engineer inside the locomotive’s cab could see. The single track running through a narrow strip of landscape is the moral equivalent of what the real engineer is aware of as he proceeds down the right of way.

Whatever ultimate size and shape my model railroad will be, it will be composed mostly of a very long sincere shelf. It will likely be wrapped around itself in some spiral fashion in order to make the best use of the space. While real railroads go from one point to another in basically a straight line, few of us have model railroad rooms that are eight feet wide and 1000 feet long.

I have learned much about model railroad planning as a result of the many, many (some would claim too many) track designs I have made. Most model railroads occupy only a couple hundred square feet of space, and the lessons such layouts teach us are commonly known. Because I am planning to build a much, much larger model layout, I’m encountering some lesser known problems and opportunities. It is my intention to record those lessons in this blog, so stay tuned.

No comments:

Post a Comment